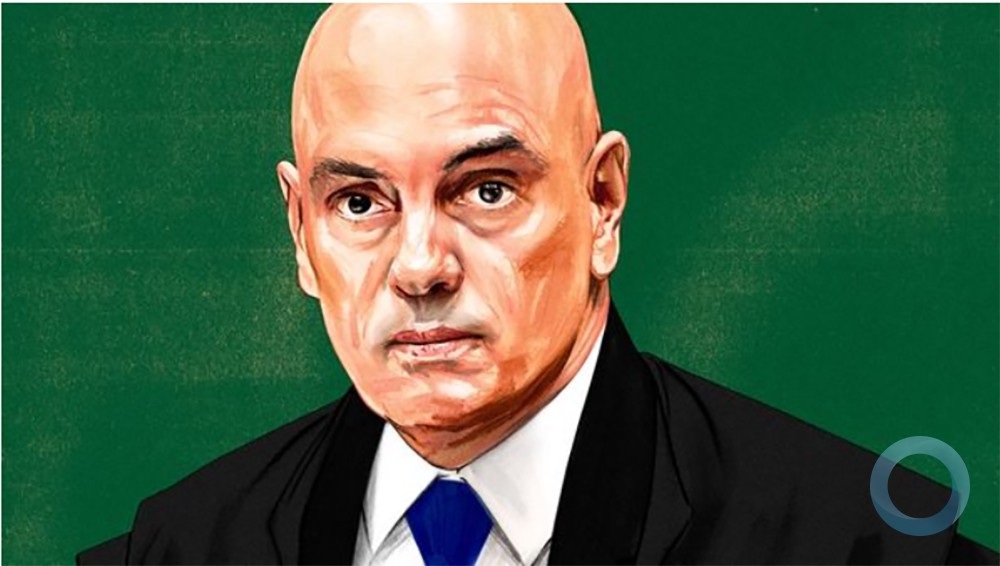

Brazil’s Alexandre de Moraes is on a crusade to cow the far right by curbing online speech

The Economist

16 April 2025

Nota DefesaNet / DefesaNet Note

O presidente do STF publicou no dia 19 uma contestação a esta reportagem . Versão em português

STF presidente published comments to this report See text in English

STF Nota à revista The Economist

Editor

Brazil’s Alexandre de Moraes is on a crusade to cow the far right by curbing online speech Only in Brazil, which endows its Federal Supreme Court (STF) with extreme power, could a judge be so prominent. As guardians of Brazil’s prolix constitution, which covers everything from health care to wages, STF judges often rule on matters which in most places are the remit of elected officials. Because of the caseload this creates, the STF allows judges to make consequential decisions individually,rather than waiting for the full bench to convene.

This gives each judge enormous visibility—and an air of celebrity. Rulings are broadcast live. The court runs a lively TikTok account.

Yet no other STF judge has a public profile to compare with Mr Moraes. He became famous during a sideline running Brazil’s electoral tribunal between 2022 and 2024, when Jair Bolsonaro, Brazil’s far-right former president, allegedly tried to organise a coup to stay in power. His investigations into Mr Bolsonaro, and a related probe he leads into online misinformation, mean that Mr Moraes rivals US Supreme Court members for the title of most powerful judge in the world.

He was appointed to the STF in 2017 while serving as justice minister in the centre-right government of Michel Temer. As a public prosecutor he had earned a reputation for ruthlessness, but he is often genial. Asked about Mr Musk and his threats, he concedes that he is “a brilliant businessman”, then adds: “I don’t waste a minute of my life thinking about him.”

What Mr Moraes does think about is unregulated online speech. His concern took root in 2018, when Mr Bolsonaro was elected president. An army captain turned congressman, Mr Bolsonaro praised Brazil’s former military dictatorship and attacked institutions that might check his power. During the campaign his son, a congressman, stated that “a soldier and a corporal” could shut down the STF.

After Mr Bolsonaro took office the threats intensified. Mr Moraes recalls an anonymous post detailing the travel plans of an STF judge and urging people to stab him at the airport. The attorney-general, a

Bolsonaro appointee, ignored complaints about the incident, and other similar ones, prompting the STF to open a probe into misinformation in March 2019. The “fake-news inquiry” was set up to investigate online content which “affects the honour and security of the Supreme Court, its members and their families”. Mr Moraes

was put in charge, bypassing the lottery system which is the norm for such appointments.

Since then, he has suspended hundreds of social-media accounts, mostly those that are pro-Bolsonaro. (The fake-news inquiry is sealed, so the total number of suspended accounts is unknown.)

Platforms are usually given mere hours to carry out court orders, and users are often not told why their profiles have been blocked. In 2024 he blocked X, Mr Musk’s social-media platform, for more than a month across Brazil, and froze the bank accounts of Starlink, Mr Musk’s satellite-internet company.

This digital crusade has made Mr Moraes a target in Washington. On top of Mr Musk’s attacks, the media company owned by President Donald Trump has sued Mr Moraes for allegedly violating free speech. The US State Department then accused Brazil of censorship.

Some members of the US Congress want to sanction him and bar him from entering the United States.

Classically radical One might expect a judge in the MAGA cross-hairs to be left-wing.

But Mr Moraes calls himself a “classical liberal” and defends republican government and a limited role for the state in the economy. He has only ever worked for centre-right politicians.

“Virtue”, he says, “is in the middle.” Brazilian leftists were furious when he was appointed to the STF because he favours privatising state-owned companies and legalising gig work, as well as the use of force to break up protests.

A more plausible explanation for Mr Moraes’s campaign is this: it’s personal. He receives constant death threats. These seem to invigorate him, and have given his rulings an absolutist edge.

“People are starting to realise that there’s not much point in threatening me. They will just waste their time—or go to jail,” he grins, hinting at draconian instincts.

Mr Moraes is empowered by Brazilian law. Like any democracy, Brazil places limits on freedom of speech, but it does so quite broadly and enforces those limits extremely harshly. Any “discrimination or prejudice” based on race, gender, sexual orientation, religion or “physical or social condition” is prohibited. Penalties for slander, defamation and libel are higher if the insults are against public officials. Yet even by Brazilian standards, the gusto with which Mr Moraes has deployed his sprawling mandate has been alarming. The fake-news inquiry, which was supposed to last just nine months, is still running six years later, and now covers attacks against any of Brazil’s democratic institutions.

Some of his targets have clearly acted beyond the law. One prominent journalist critical of Mr Bolsonaro had her face transposed onto pornographic images; Mr Bolsonaro and his fans insinuated that she obtained interviews in exchange for sex. Carla Zambelli, a Bolsonarista congresswoman, chased a pro-Lula voter while waving a gun. The volume of unhinged content on the Brazilian internet isoverwhelming.

But Mr Moraes has sometimes gravely over-reached. In May 2019 he forced a news outlet to take down an article showing potential links between an STF judge and a businessman who had been convicted for bribery. Public outcry forced him to reverse the order. In August 2022, after a newspaper published the private messages of some Bolsonarista businessmen, Mr Moraes ordered police to raid the mens’ homes, blocked their bank accounts and shut down their social-media pages; one of the men had written that “I prefer a coup to the return of [the left-wing Workers’ Party]”. Again, Mr Moraes stopped investigating six of the eight businessmen after a public backlash.

Questioned about these cases, Mr Moraes says he changed his mind after receiving more information. He insists that he is merely applying the law. “Because of the ideological polarisation that exists today in Brazil, some people don’t realise that my decisions are technical, not political,” he says. Yet his rulings can hint at personal caprice. In July 2023 a Bolsonarista family assailed Mr Moraes at an airport in Rome, allegedly slapping his son.

The family was investigated for calumny and their house was raided. Charges were dropped only after the family apologised to Mr Moraes. Shoeing the truth Mr Moraes says that Brazil is “in the vanguard” when it comes to taming social media. He criticises American politicians and businessmen who “hide behind the false idea that freedom of speech has no limits in order to maintain a business model that generates a lot of money”. “A new extremist digital populism has emerged, led by the extreme right,” he says. “And they exploit something that Goebbels used to say during the Nazi era: a lie told a thousand times becomes a truth.” He believes that if social media are not checked, “you will get a dictatorship here, a dictatorship there, extremism, the return of fascism.”

Freedom House, a think-tank in Washington, calls Brazil a “swing state” because it is one of just a few large democracies that have not yet taken legislative steps to regulate speech on the internet, leaving that work to judges. The rest of the world is watching Brazil, and Mr Moraes, closely.

Mr Bolsonaro may go to prison this year. His trial begins soon. If he is jailed, Brazilian tolerance for Mr Moraes’s heavy hand may wane.

“I worry about people who have an authoritarian bias,” says a prominent left-wing intellectual, referring to Mr Moraes’s iron-fisted rulings. “When the wheel turns” and a domineering judge with different views sits on the almighty STF, “I could be sent to jail.”